|

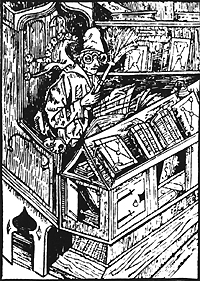

"Bibliomaniac" attributed to Albrecht Dürer, from the Narrenschiff of Sebastian Brant (first published 1494) |

on

culture, history,

"civilization, given to all races, not just one" |

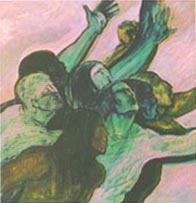

"Protest,"

by Armand Szainer

|

|

These two images seem to represent stark and all-too-familiar opposites: •

on the one side, the cloistered academic (figuratively and literally

nearsighted); on the other, the common people; The "Büchernarr"—bibliomaniac, literally, "book fool"—was the first in the parade of figures that filled Sebastian Brant's immensely popular Narrenschiff, or Ship of Fools. Indeed, he was a parody within a parody, a failure even by his own standards. Not only was he isolated from the world, but he wasn't even truly learned. The heading entitled, "Of Useless Books" ("Von unnutzen Buchern"), explained that he had pride of place in the ship because he had many books that he neither read nor understood ("Den Vordantz hat man mir gelan/Dann ich on nutz vil buecher han/Die ich nit lyß und nyt verstan"). The stereotype of an opposition between culture and action, and tradition and modernity, has proven extraordinarily resilient, and it is perhaps a particular danger at Hampshire College, which prides itself on concern with contemporary life and social values. This need not be the case. Many of the great radical thinkers of the modern age, from Karl Marx to W. E. B. Du Bois, saw no contradiction between being admirers of classical culture and social change, and they did not demand an art that neatly reflected their political convictions. For that matter, when the founders of Hampshire College set out "To reorient the college as a corporate citizen, active in the civic problems and processes of its surrounding community," they did not presume to discard the past. The goal, as they put it, was to

The story of the painter of "Protest" [2] illustrates how the tumultuous history of the twentieth century impinged on one man's life and art, from Europe to New England. Armand Szainer (1914-1998) was born into a Jewish family in Dzialoszyn, Poland, and raised in Plauen, Germany, where his father worked as a Hebrew teacher, calligrapher, and folk carver. He had been accepted into and hoped to attend the Bauhaus, but when the Nazis came to power in 1933, he emigrated to France and worked as a painter-decorator until being drafted into the army at the outbreak of the war. After the Germans took his division captive, it was sent to Stalag XI B, where he was forced to work as a lumberjack in a special camp for Jewish prisoners. He was liberated five years later, only minutes before he was scheduled to be executed for leading an unsuccessful escape. Upon returning to Paris, he learned that almost all his family had perished in the war. One brother survived in hiding. Another died in Auschwitz but left behind a unique legacy. While in a transit camp, he occupied his time in a skill the father had taught the sons: carving a continuous wooden chain from a single piece of wood. The chain, which depicts episodes of Jewish history and camp life, is now in a Holocaust collection in Israel. Armand Szainer worked as a stage designer for the Yiddish Art Theater in Paris and Brussels and continued his study of art. In 1947, he married Sylvia Kostmann (1912-1983), a physician and fellow immigrant from Poland. In the early 1950s, they emigrated to New Hampshire, where his sisters now lived. Szainer worked as a commercial artist, painting signs and making store-window displays, but he also managed to continue his studies. Increasingly, he sought to devote himself to his own art. In the course of the 1960s and 1970s, he established himself as an artist and a presence in the New England art scene: He painted and worked in collage and a wide range of sculptural media. He served as a member or officer of numerous regional artistic organizations and for a decade edited Studio Potter. He also became a teacher at several New Hampshire institutions of higher learning, notably Notre Dame College, whose faculty he joined in 1968. Szainer sought in his work to combine the historical and the transcendent, as he told an interviewer in the 1980s. Civilization must struggle against the eternal forces of ignorance and natural decay, but in the modern age, a third enemy has joined the fray: the self-destructive capacity of the human race, epitomized by the machine: "no matter how far man gets technologically, he ends up back with himself, bringing forth new life from himself . . . There is also spirituality and love, and you cannot have any machine for that." [3] Nonetheless, he was no enemy of technology, as such. One of his major works, accomplished in partnership with his frequent collaborator, the ceramist and sculptor Gerry Williams—later the first artist-laureate of New Hampshire—was the large relief, "Man and Industry," commissioned by the International Paper Box Company in Nashua.

In his later years, Szainer turned increasingly to Jewish themes. Among his major public works, for example, was a Holocaust memorial (above). But he was always motivated by the creative tension between the particular and the universally human. It was no accident that his home and studio were filled with art from a host of cultures. Thus he explained a symbol in one of his murals, inspired by the famed Mexican muralist José Orozco, as signifying "civilization, given to all races, not just one." As he added, "Of course, the Nazis are always in the back of my mind." [4] Szainer's teaching style, too, resonates with the ideals of Hampshire College. As a colleague on artistic juries put it, "He would go over the drawing or photograph or painting inch by inch. Others would say right away, 'We don't want this,' and that would be the end of it—but not Armand. He would always point out the positive points, as well as the deficiencies in a work. You knew he would be honest and fair, not necessarily easy on you either. But he was always very kind and encouraging and very giving of his time. He would make sure people knew where to find him if they needed help." [5] As much as Szainer valued process and diagnostics, he at the same time stressed the need for closure, also a valuable lesson at Hampshire. Sculptor Jane Kaufmann lists Szainer's simple advice among the the memorable lessons she learned as a student: "End up with something." Sylvie Kostmann spent the war in hiding in France, but few other family members survived. The story of her cousin, Leon Greif (1905-1999), from Sambor in Galicia, was among the most dramatic. Like Armand Szainer, he had artistic inclinations. Although he was a talented musician with hopes of becoming a concert pianist, the social pressures of an early first marriage led him to pursue a career in medicine and he went to France for training. After completing a thesis in neuro-psychiatry on writer's cramp, he went to work for the Curie Foundation. When the war broke out, he joined the army and was wounded and decorated. Like Szainer, he was captured when his entire unit fell into German hands. Thanks to a bold deception, however, he was released from prison camp, after which he returned to Paris, where he passed as an Aryan. He met a fellow Polish immigrant, Malvina Zien, and the two soon gravitated toward the Resistance. They took the code names Jacques and Jacqueline and joined the leftist FTP-MOI—Francs-Tireurs et Partisans-Main d'Oeuvre Immigrée—drawn mainly from Jewish immigrants. Because the group was dedicated to direct action at a time when many other factions were reserving their blows for a strategically more favorable time, it provoked an especially fierce reaction from the occupiers as well as a certain disquiet within the Resistance itself. In late 1942, "Jacques" escaped arrest by a mere chance, but "Jacqueline" was captured in the raid. Although given up for dead by all who knew her, she emerged from the Gestapo prisons half a year later, and the couple took up life together on the run. Soon afterwards, the Nazis finally broke up the FTP-MOI. The history of the group and its destruction are the subject of the controversial documentary film, "Terrorists in Retirement" (French 1985; US release 2001), by Mosco Boucault. Twenty-three members were executed in late February 1944. A few weeks earlier, Greif himself was betrayed and arrested. Ironically, his origins saved him from death. When stopped by the authorities and asked why he was carrying false papers, he had the presence of mind to confess that he was a Jew. Had the Gestapo identified him as a "terrorist," he would have been shot. Instead, he was deported to Auschwitz. Luck, professional skills, and political connections enabled him to endure life in the camp. Of the 1214 persons deported in his convoy, 985 were gassed immediately upon arrival, and only 26—Greif among them—survived the war.[6] After liberation, he was reunited with Jacqueline. The couple had three sons, each of whom, in his way, carried on the family engagement with social issues and culture. • Michel Greif (b. 1945) studied engineering at the École Polytechnique and obtained a doctorate in geophysics from the University of Paris. Today he is Associate Professor of Logistics and Operations Management at the École HEC (Paris) and Associate Director at the Proconseil Consulting Group. He is the author of The Visual Factory: Building Participation Through Shared Information (1989; English version 1991). The work, which has been translated into several languages and become a staple of "lean production" training, calls for the creation of a "transparent" workplace in which workers, supervisors, and management have equal access to vital information. In effect it argues that democratization and decentralization of the enterprise are essential to efficiency and global competitiveness alike. • Olivier Greif (1950-2000) studied piano and composition at the Conservatoire Nationale in Paris and the Juilliard School in New York. Both piano composition and performance were central to his musical sensibility, from his first youthful efforts (e.g., the Second Sonata, 1964) to his maturity. The interplay of text and music was among his major theoretical and practical concerns, and he produced works based on the oeuvres of such varied poets as Donne, Blake, Heine, Hölderlin, Musset, Paul Bowles, and Li T'ai Po. Increasingly interested in questions of spirituality, he immersed himself in the study of world religions and in particular delved into Indian traditions. Among the fruits of his sustained engagement with the horrors of the twentieth century were "Bomben auf Engelland" (for voice, saxophone, and piano), "Hiroshima/Nagasaki" (for mixed choir) , "Todesfuge" (on the poem by Paul Celan, for string quartet and voice), and "Lettres de Westerbork" (from the correspondence of deportee Etty Hillesum as well as the Psalms, for female voice and two violins), dedicated to his father. Following his tragic and unexpected death at the age of 50, friends and family established the Association Olivier Greif in his memory, under the sponsorship of his former teacher, Luciano Berio. (The website includes excerpts from compositions and interviews.) sonata Summary of his career and review of the Memorial Concert, Paris, May 2001, from Le Monde. Memorial Concert, Cordes-sur-Ciel, August 2001. • The eldest son, Jean-Jacques Greif (b. 1944) became a journalist who has covered topics ranging from Nancy Reagan to the killing of Amadou Diallo by New York Police. In recent years, he became an author of historical stories for young adults. In particular, he has explored the history of his family in a series of fictionalized biographies, all in the series, "Collection Médium" (Paris: l'école des loisirs) •

Le

ring de la mort (1998) Much of Greif's time is now dedicated to educational outreach and community service. He participates in debates and colloquia and frequently speaks in schools, where his presentations have been very successful in engaging the students on both a personal and an intellectual level. One summary of his novels could also serve to summarize the common efforts of his family, and of artists such as Armand Szainer. For that matter, it speaks to the goals of all of us who teach and learn about the past: "...[to]

take to the bed of history in order to nourish a humanistic vision

of the world, an irresistible desire for knowledge and [a desire]

to keep alive the memory of human beings."

|

||||||||||

|

|

|

last

updated

20 August, 2002

|