Can you find the hidden images on this page?

Paris 2054. Live forever or die trying. The tagline of Christian Volckman’s animated film Renaissance anticipates little more than a gratuitous melodrama. And to some extent the expectation is realized. The plot of Renaissance is almost embarrassingly cliché. Within the barricaded borders of a future Paris, a young genius recruited to work for the corrupt cosmetic conglomerate Avalon disappears. A disillusioned tough-as-nails cop scours the city until he unravels the mysteries of the crooked customers behind a search for eternal life. Rather than this uninspired series of events, it is the Paris Volckman has created that makes his film worth watching. Though inhabited by hackneyed characters who drop one-liners stale enough to make you wince, Volckman’s 2054 Paris is stunning. It is a mosaic of classic Parisian symbols—the Eiffel Tower, Notre Dame, the Seine, Haussmannian boulevards—and an invented future city dominated by architectural transparency. In this Paris light and space are rare commodities. Glass structures are windows that shed light into dark underground corners.

The dominance of glass in the visual language of Renaissance provokes questions about architecture, transparency and security in ways that the clumsy plot cannot. The glass that lines the banks of the Seine, covers the roadways as extended sidewalks, and surrounds the base of Notre Dame is more dynamic, more captivating than a car chase through central Paris. The rather mundane chase ends with a crash in a public space beneath Notre Dame. Volckman’s version the most famous gothic cathedral in Paris floats on a transparent ground, a glass divide between above and below, outside and inside. Pedestrians who seem to be walking on air as they cross the Île de la Cité are fully visible from underground. The scene is visually astonishing. But as a prospective (if farfetched) reality, the beauty of this architecture fades into an unsettled stirring of fear. Sure, the glass flooring allows light to wash over underground spaces. The amount of public space in the city has been exponentially increased. But this illusion of continuity, of a connection between light and dark, comes at the cost of security.

In the film, the subject of the chase climbs the stairs that connect the spaces on either side of the glass divide, and shoots bullets at the glass ground, toward our friend—the tough-as-nails cop—below. Dozens of pedestrians above and below the transparent divide run from the shooter in a grand spectacle of pandemonium and fear. The melodrama of this series of events not so subtly points out a serious flaw in the use of glass as a major structural element in dystopian urban planning—and maybe even in the use of glass as a security measure in 2008. Today there are security risks beyond the fragility of glass and transparency. Public spaces made out of glass simultaneously force every occupant of the space to become both a Panopticon security guard and a voyeur. Through glass, you could catch someone picking a pocket or you could spot someone picking his nose.

So why would Christian Volckman choose to create a Paris in which glass becomes a character in a city filled with suspicion and cynicism? Perhaps it was simply a challenge leveled at the traditions of computer animation: how can glass be animated as a tangible, concrete architecture that doesn’t simply fade into air? It is more likely, though, that the manipulation of transparency throughout the film is more than an exercise in animation, but rather an extension of troubled politics into an architectural arena. It is a solution to expanding a city with rapidly disappearing space. Glass can be either a mirror or a window; a reflection of one’s self or a refraction of a bigger whole. The transparent additions to Paris in Renaissance might be an ironic gesture towards the film’s atmosphere of betrayal and mystery, of hidden dealings within the dystopia of 2054—the general lack of political transparency. Or it might be a more genuine translation of the secrets and layers that qualify this vision of the future. A transparent space distorts what it covers and surrounds; it bends light and creates a false sense of visibility, perhaps even a false sense of security.

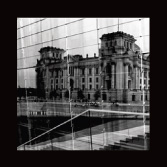

Volckman’s vision of government secrecy and corporate conspiracies is hardly an image limited to the not-so-distant future. It is also the stuff of the immediate past and the present. The link between political and architectural transparency has long been a metaphor used to reassure a public of political security, of openness and democracy (click here to view a related article within the journal on post-war west German architecture). The recent addition to Dublin’s Palladian parliament building, the Leinster House Pavilion, is a glass entryway specifically designed to maintain security over traffic in and out of the government building. A contemporary example political transparency showcased in political architecture, the Leinster House Pavilion simultaneously exposes and protects.

The architecture of transparency in contemporary politics offers a figurative translation of the connection between glass spaces and security. The current American political arena has been so much characterized by irresponsible spending that Democrat Barack Obama and Republican Tom Coburn unanimously passed the Federal Funding Accountability and Transparency Act of 2006 through the senate, house, and the president’s office. The act promises to develop transparency and security by exposing federal “sweetheart deals” to the sunlight. Any average American can access the Web site and sift through records of federal spending of tax dollars. The site establishes a level of accessibility meant to discourage federal waste, fraud and abuse. But like the urban planning in Renaissance, in which pedestrians walk on glass over lanes of traffic without fear of collapse, fracture or unwanted exposure, Obama and Coburn’s hopeful vision of a transparent political process is fragile. It could easily develop into a tool that exposes corruption without fixing it, a Panopticon with no means of inflicting consequences on rule-breakers. How depressingly easy it is to convert hope into anxiety.

This discussion of security and transparent structures leads to questions of surveillance and visibility. A security camera, for example, echoes the duality inherent in a glass public space—it can function as an active search for wrongdoing and as an invasion of privacy. A security camera can scrounge up essential details of a person’s life as well as mundane trivialities. It can see through a person with its omniscience. The primary intent when most cities install closed circuit television (CCTV) systems is to reduce crime. This understanding of CCTV assumes that cameras would deter misdemeanors simply because the cameras exist—that criminals would think twice before committing a crime because they know cameras are there. But while it is true that security camera footage can help to catch the identity of a criminal after the deed has been done, the mere presence of security cameras is not yet effective in lowering crime rates. In many cases, camera footage does little more than splash a belated spectacle of violence and crime into primetime news. Regardless of the effectiveness of security cameras, they are working toward creating a transparent society. The colossal network of security cameras in most urban spaces is rapidly realizing George Orwell’s dystopian vision of the future.

|

by Jocie Edens and Molly McLeod

|

|

|

|||||||||||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

||||||||

|

|

|

|

||||||||||

|

|

|

|||||||||||

|

|

||||||||||||

|

|

|

|||||||||||

|

|

||||||||||||

|

|

|

|

||||||||||

|

|

|

|||||||||||

|

|

|

|||||||||||

|

|

||||||||||||

|

|

||||||||||||

|

|

|

|||||||||||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|